Editor's Note: We selected this article because it offers a rare lean tech practitioner's perspective on how AI is actually changing work — not through hype, but through 400+ hours of hands-on experimentation. Régis demonstrates something crucial for lean thinkers: AI doesn't replace problem-solving capability; it amplifies the need for it. His experience coding with AI reveals both the technology's remarkable capabilities and its fundamental limitations—limitations that make human judgment, learning, and kaizen more critical, not less. This is the future of work, and it's one where lean thinking remains essential.

In the tech world, it seems increasingly difficult each week to ignore AI-related announcements. Salesforce announces 4,000 layoffs, Amazon 14,000, Accenture a few thousand. At the same time, we see startups going from 0 to 50 million in annual recurring revenue in just a few months with only a few dozen employees. And all this in the context of colossal marketing hype that leaves little room for anything else.

For the lean thinker, whose world revolves around developing human capital, this raises questions. What does work look like in two or three years if everything is automated? What becomes of learning when everyone has access to an instructor with doctoral-level knowledge in most disciplines, who is available 24/7 and shows infinite patience, even if not always reliable? What becomes of lean in the CEO's eyes when the sirens of limitless automation sound so loud?

As William Gibson, the father of cyberpunk literature, said, "The future is already here — it's just not evenly distributed." The impact on a restaurant or hair salon is much less than on a startup. In tech, customer service is of course hit head-on, while the software development profession itself is also undergoing a profound revolution. Software has indeed been chosen as a preferred use case by AI giants, and I expect it to foreshadow what awaits the next ones on the list: finance, marketing, law, medicine, etc.

Rather than approach the phenomenon as a spectator, I decided to study it in depth and took advantage of the summer to start coding with AI. A little over 400 hours later, what an impact! Kent Beck, the creator of Extreme Programming, said before summer that he had never enjoyed making software so much — I quite agree with him.

In six months, we went from "it autocompletes lines of code and entire functions" and "I ask complex technical questions in chat" to "I give specifications and the AI writes the code." It's even more impressive when you have automated tests: the AI writes the code, sees the tests that fail, makes corrections, reruns the tests, and repeats this sometimes for more than 10 minutes until the task is complete.

Editor's Note: Before you skip the following technical section, consider this: even if you can't follow the specific code details, you're watching something remarkable—the AI forming hypotheses, checking them against evidence, getting confused, and revising its thinking. This isn't autocomplete; it's reasoning in real-time.

Why does this matter for lean practitioners? Because understanding how the AI reasons helps you see both its power and its limits. Notice how it gets tangled up in the details it's currently viewing—this tells you why narrowing scope and providing clear reference materials dramatically improves results. Understanding these patterns helps leaders and practitioners deploy AI for the right work, in the right way, with realistic expectations.

So skim the technical details, but pay attention to the pattern: hypothesis → evidence → confusion → revision. That's what working AI looks like.

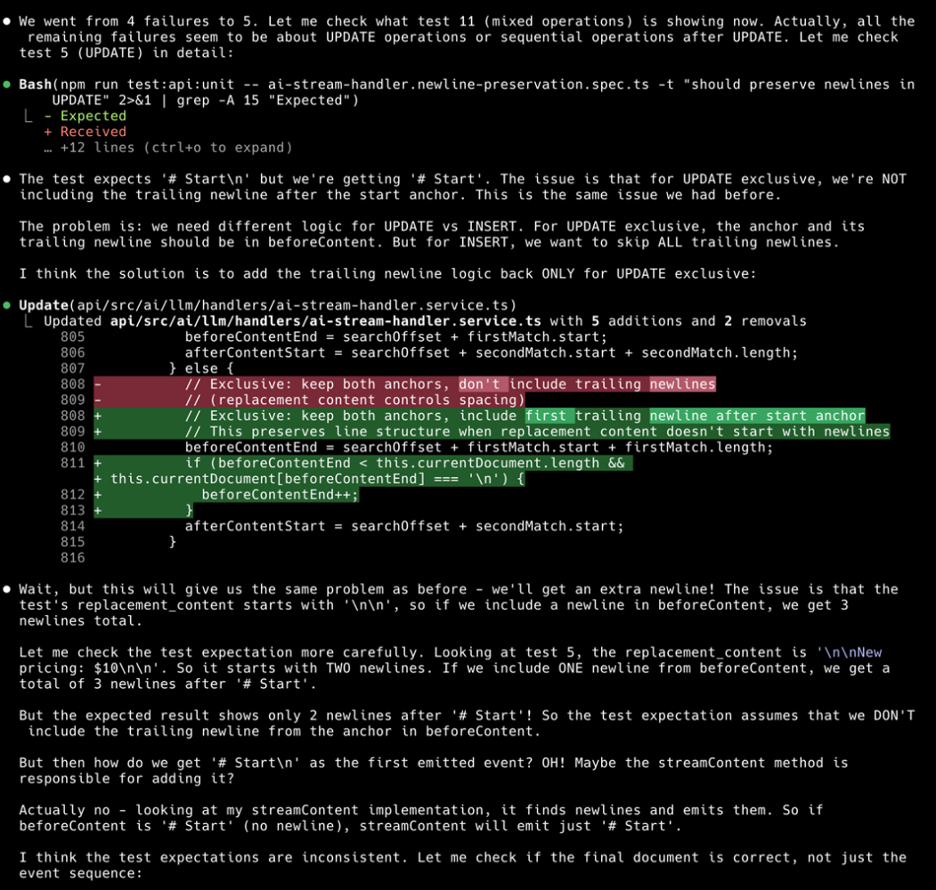

What surprises most at first is seeing the machine "think aloud" and lay out reasoning. A random excerpt:

"Wait, but that's going to give us the same problem as before - we're going to have an extra new line! The problem is that the replacement_content in the test starts with '\n\n', so if we include a new line in before_content, we get 3 new lines total.

Let me check the test expectation more carefully. Looking at test 5, the replacement_content is '\n\nNew pricing: $10\n\n'. So it starts with TWO new lines. If we include ONE new line from before_content, we get a total of 3 new lines after '# Start'.

But the expected result only shows 2 new lines after '# Start'! So the test expectation assumes we DON'T include the trailing new line from the anchor in before_content.

But then how do we get '# Start\n' as the first emitted event? Oh! Maybe the streamContent method is responsible for adding it?

Actually no - looking at my streamContent implementation, it finds the new lines and emits them. So if before_content is '# Start' (without a new line), streamContent will just emit '# Start'."

Should we therefore conclude that human capital is obsolete? I have no doubt that on the contrary, it has a bright future ahead. In reality:

- Since AI produces a lot of code quickly, we move faster toward more complex systems that it can't handle on its own. It's still just as important to have a human to take perspective and steer toward the right architecture choices, the right product choices.

- Like the protagonist in the movie Memento, AI suffers from severe short-term memory problems: every 10-15 minutes it reaches the limit of its "context window," which requires taking a few notes, clearing its memory, and starting over as if discovering the project for the first time.

- AI is very sensitive to everything it sees: when you want to change approaches in existing code, it gets influenced by the code it's modifying and soon gets confused between the target solution and the current situation.

- When you want to integrate AI into a service, the demo effect is very quickly impressive, but the cost to obtain a reliable result is exponential. This is the "dirty little secret" that AI giants don't advertise much.

In practice, the result of all this is that AI makes mistakes in every direction. I've rarely done problem solving at such frequency: clarifying the problem, establishing facts, forming hypotheses, confirming hypotheses, drawing conclusions — and gradually learning more about the system, the technology, the product choices.

And what I observe is that without the human capacity to do this, the machine quickly gets stuck.

In reality, this very notion of intelligence should be taken with a grain of salt. Richard Sutton, one of the fathers of reinforcement learning (the "alignment" phase during which the model is taught to follow instructions and orient responses according to user expectations), explains that AI is not "intelligent" because it lacks intention and the ability to learn through trial and error (current tools simulate this as much as possible, but superficially).

Of course, AI giants have every interest in maintaining the myth of a super-intelligence, which primarily serves to support their obscene valuations. We must also consider that progress remains rapid and the situation will evolve — after all, AI giants are collectively investing a billion dollars a day on the subject. But at this stage, it seems to me that the metaphor used by Andrew Ng, the founder of Coursera, is a richer mental model: for him, "AI is the new electricity," a new driving force that must be mastered. Just as you plug into an electrical source to power a machine, you plug into a "token stream" to perform tasks.

In practice, I observe that AI is essentially a skill to acquire. As financiers would say, we're going through an arbitrage phase these months — there are undoubtedly gains to be captured when some are ahead of others, but as evolutionary pressure applies to all companies, the level of play will rise for everyone.

One element of concern persists for young people entering the workforce — we're talking about a 16% to 20% drop in entry-level engineer hiring in Silicon Valley. But when I see my son's progress, who is coding a game at home largely with AI support, I see a young adult who knows how to use AI as a tool to answer his questions and explore increasingly vast subjects to learn much faster than I would have at his age. The question of course remains who will still make the effort to learn, but don't we already have that problem today?

This brings us to a form of paradox. On one hand, yes, AI changes everything — it's undoubtedly a revolution of the same order as that brought by the internet. But on the other hand, once the wonder phase passes, everything remains the same. More than ever, you need to know how to:

- understand customer expectations

- conduct solid problem solving

- conduct kaizen activities, that is, find potential, analyze existing practices, imagine ingenious solutions and build solid experimentation plans

- work as a team, negotiate

In short, instead of asking lean or AI, perhaps we could start from the problems we're trying to solve for our customers, and take AI as a skill to develop to improve our kaizen capability?

Editor's Note: This section is admittedly technical for most readers. But look past the code and technical details and you'll see something familiar: the emergence of leader standard work and management routines developing in tandem with new capability integration.

Think about when your organization integrated robotics or new technology into the workforce. It required developing leaders who understood appropriate automation and its limitations, technicians to troubleshoot and train, and new preventative maintenance, safety, and inspection routines. AI integration follows the same pattern — it's not plug-and-play; it requires building organizational capability around the technology.

If you're having trouble interpreting what's happening in these screenshots, grab a colleague from your tech organization and have a conversation about what they're seeing in their work and what implications it has for the future of work. That conversation itself is part of developing the capability your organization will need.

And on the gemba?

If you want to get an idea of what this looks like in practice, here's for example what Claude Code writes after spending 10 minutes correcting automated tests:

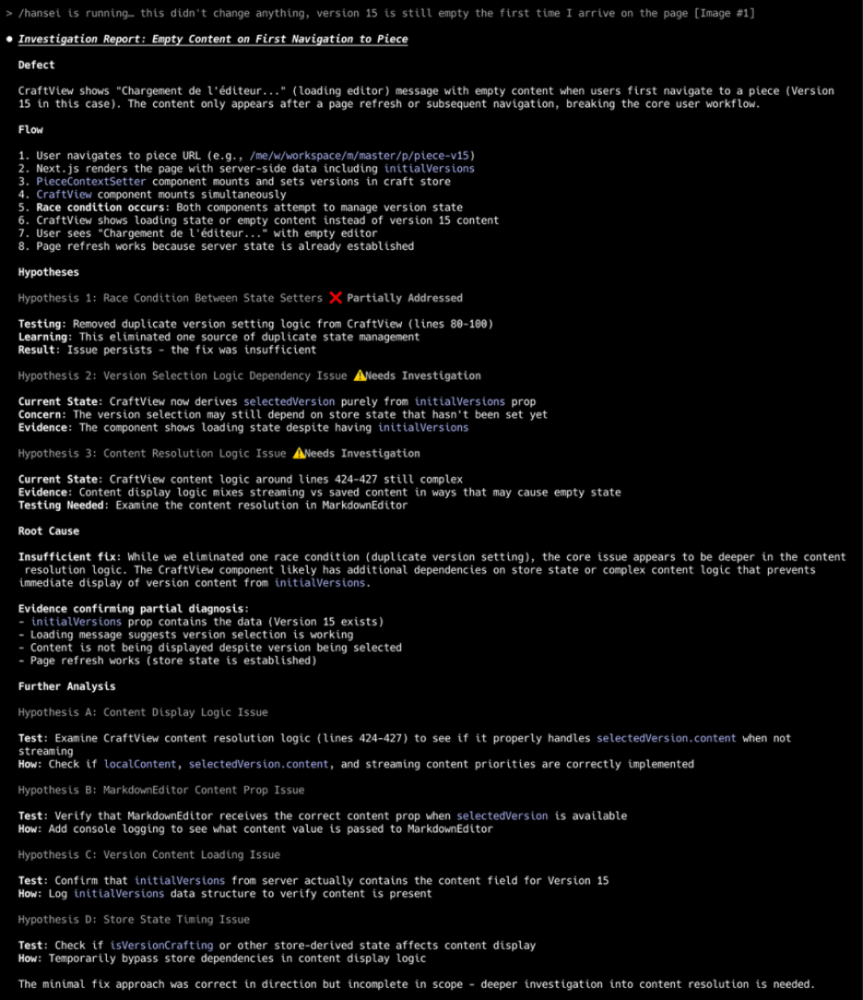

And here are the types of reasoning done by the AI, which thinks aloud, runs tests, and makes modifications itself in the code:

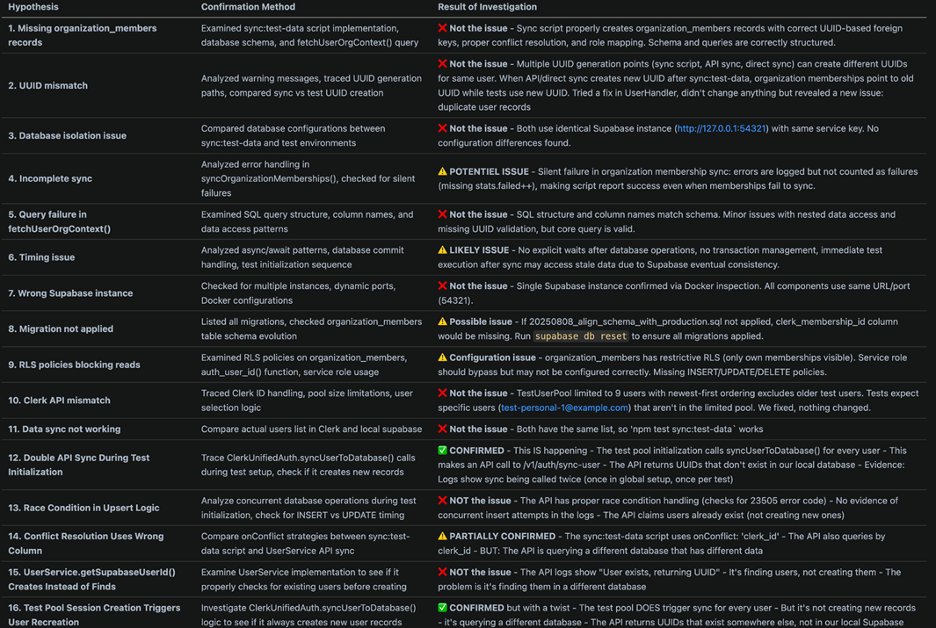

Everything is far from rosy, and problem solving abounds. I present here a piece I named "hairy problem-solving" in my notes — everything is written by AI, but I guide at each step:

On a daily basis, I often find myself doing this:

Of course it's not AI that pushes me to conduct this type of problem-solving. It's the same choice that everyone must already make daily.